Nowadays it's pretty common to use a bus compressor over your whole mix. This can add those mythical qualities like 'glue' or 'warmth'. Or a bus compressor can make things louder, not that there's anything wrong with that. But what happens when you need to send someone stems of your mix? If you just print the individual elements through that magical bus compressor, your stems won't sound right when you combine them later. The guitars won't be reacting to the snare drum hits, the vocals won't duck the guitars, and the kick drum won't combine with the bass guitar to create that platinum record sound. So what can we do? If you have a compressor with a sidechain input, it's pretty easy.

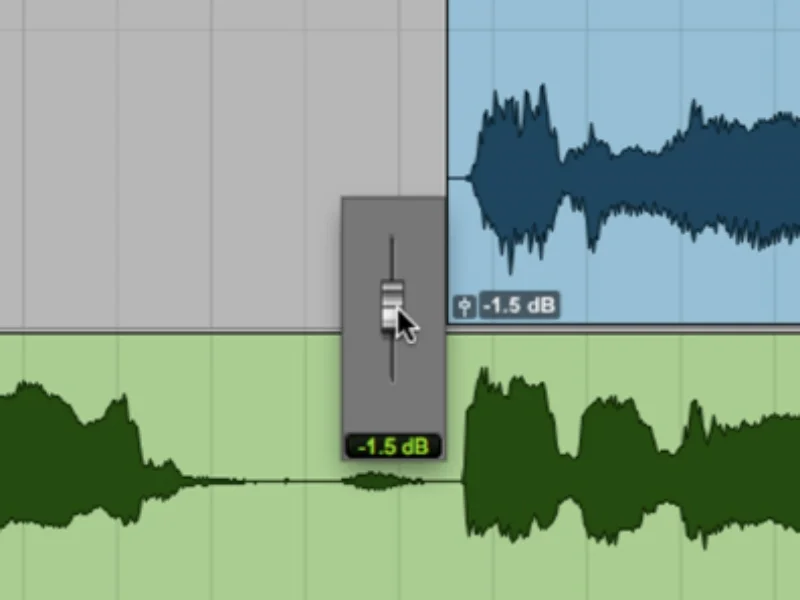

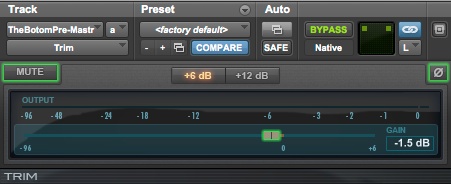

Print your whole mix, but don't print it through your buss compressor. Bypass that, and you'll have a 2-mix of your song minus any compression. Go ahead and assign that printed 2-track to the sidechain input of your buss compressor. Now when you go to print stems, the compressor will be responding just as it would have with everything combined, but it is now showing it's total effect on individual elements of the mix!

Click to enlarge