So far it's been lovely being in Colombia. Cartagena seems like a very European town, especially because we're staying in the Colonial District, which is inside a huge walled compound meant to keep out pirates. It's very hot and extremely humid, so I try to limit my solo walks to only an hour or two. Wifi is spotty around here, so I'm keeping this brief.

Avid EQIII Hidden Feature

If you use Pro Tools, then you're probably very familiar with the stock EQIII 7-band eq that comes standard with Pro Tools. It's a useful eq, though not with any sort of "character", but sometimes that's a good thing. Very recently I came across a key command trick to get access to a hidden feature of the EQIII. If you hold down Shift and Control while you adjust a frequency band, the band goes into solo mode and you can hear whatever is only inside that narrow band. It's a trick that is common to Brainworx eq's, but I had no idea that you could do this with the stock Avid eq. Here's a little video showing it in action.

Make Things Wider By Making Them Mono

Ever since stereo records came out in the 1960s people have been trying to get their mixes to sound as wide as possible. People think that having all their tracks recorded in stereo means that their mixes will be guaranteed to be wide, but that's usually the opposite of the way things turn out. If you're guitars are panned hard left and hard right, and so are your pianos and drums and everything else, then there's no contrast in your mix. Everything is in both speakers and the ear has trouble separating your mix.

Contrast can come from many different avenues, and taking mono sources and panning them around is one of the easiest and best ways of creating contrast in a mix. If you are given source files that are all stereo, make sure they're truly stereo, and not just a stereo track. If the source isn't truly stereo, consider throwing away one side and panning the remainder to help it sit in the mix or stick out of the mix. You could also use any number of plugins to reduce the stereo width of a track. Most plugins that aim to widen the stereo field can also reduce the stereo field, so don't think of them as one-trick ponies. Confining the stereo width of an instrument can help you place it in a specific area of the stereo spectrum.

Slate Virtual Tape Machine RTAS vs AAX

As a frequent adopter of new technology, I quite like living on the bleeding edge, but that's not always an option for me, whether due to fiscal responsibility or plain-old...responsibility. Hence why I'm still using Pro Tools 10, instead of Pro Tools 11, which has been out for almost a year now. The reason why I've been holding out so long is that, with Pro Tools 11, Avid have decided that only AAX plugins will work in their software. This puts the onus on the myriad plugin manufacturers to recode all their plugins for AAX 64bit compatibility. You see, in introducing Pro Tools 10, Avid also introduced their new plugin format, AAX, and said that in the future Pro Tools will no longer support the older RTAS system of code. Fortunately Avid decided that Pro Tools 10 would allow both RTAS and AAX formats, so as to lesson the shock that would come from a sudden shift to a whole new format. So while I wait for all my favorite plugins to be reintroduced in 64bit AAX format, I'm sticking with Pro Tools 10.

It just so happens that at this point, the only plugins I'm waiting for are Slate Digital's. I use them in all my mixes, and they sound so damn good that I wouldn't want to be without them if I had my druthers. Meanwhile, Slate Digital has done a rather odd thing, and they have released public betas for some of their plugins, most notably their aptly named Virtual Tape Machine. If I were to go ahead and install beta software (there's a reason it's called the 'bleeding' edge) I could take advantage of Slate Digital's claim that their newly recoded plugins have been optimized and now take less CPU resources. While I'm happy to hear that, I would have hoped that all software manufacturers try to optimize their software pro forma. So, how does the new AAX versions stack up against the older RTAS versions?

As you can see, I opened up a session that had 5-6 instances of Virtual Tape Machine, and took screenshots both before and after I updated to their beta software. I was hoping that there'd be a marked improvement in VTM's system usage, and indeed there seems to be a 10% lesser load after updating to the AAX beta versions. The great news is that that is a 10% lighter load for the entire session, meaning I can now use other plugins as well as VTM and potentially be at the same amount of usage as I was before updating VTM.

Favorite EQs Part 1

When it comes to choosing an EQ, I find that there are two different outcomes I'm looking for, and that will steer me towards one of two genres of EQ. For instance, there are occasionally problems with a track where EQ is the best way to deal with things, whether the problems be ringing, boominess, or a general buildup of frequencies that I want to eliminate. In those instances I gravitate towards very clean-sounding surgical EQs. The Maag EQ4, by Plugin Alliance, is nowhere near being in that camp! This EQ is colorful (obviously, look at those knobs), and is drop dead simple to use, but the simplistic controls mask a very deep plugin.

As you can see, the controls are very sparse, mostly consisting of a fixed frequency controlled by a gain knob. That may seem very limiting, but it's an extremely well thought out design. The gain is stepped in .5db clicks, and I never thought I'd say this but I can totally hear a half decibel change in many of the bands. Adding .5db at 2.5kHz and 40Hz makes kicks and snares more powerful. Adding .5db at 650Hz and cutting .5db at 2.5kHz makes electric guitars less buzzy and sit better in some songs. I sometimes find myself adding a decibel or less of just one frequency band, and moving on to the next track.

The main reason I bought this plugin is because of the peculiar Air Band, which you can see goes all the way up to 40kHz, way past what humans can hear. I don't know what kind of voodoo is in this thing, but I can add 4-5db of stuff only dogs and bats hear, and it sounds amazing. I may be adding gain to a shelf that high, but it's affects reach into the high end of human hearing, and it's pretty obvious to hear what you're doing. I tend to pop this plugin on vocals, acoustic guitars or horns, set the Air Band to 40kHz and raise the gain til it sounds angelic, then back the gain off a bit. We can't have things sounding too angelic, can we?

It wasn't until after I'd demoed the EQ4 and bought it did I spend much time messing with the other bands (the Air Band is that good!), since I thought the choice of fixed frequencies was too limiting. While the EQ4 doesn't always work out, it's a beautiful sounding bit of gear when it does. The amazing/hidden genius of this plugin lies at the extreme low end, not just the extreme high end. The Sub knob isn't labeled with a frequency, but I've heard that it operates at 10Hz. That's right, there's another range you can control that is outside of human hearing, this time it's subsonic rumble.

All in all, this is a great sounding and very easy to use EQ, and I find myself using it a lot on vocals, pianos, acoustic guitars, and even on my mix bus.

Quickly Hide Tracks in Large Pro Tools Sessions

When working in very large sessions, it can be very easy to get lost in the sheer number of tracks. In a post-production mixing environment there are usually lots of tracks being routed to many different subgroups and output summing assignments. I have a template that I've set up for working in 5.1 surround sound, and you can see a glimpse of the mix window above. As you can see, there are 141 tracks in the session. While I may not use all of them, the template is set up with that number because it's not uncommon to end up somewhere near that many tracks. Daunting, yes, but with color coding and a clear naming scheme you can quickly get your orientation. Here's a little tip to quickly hide all the tracks you don't want to see, which is very useful when you've done all your editing.

Here's a look at some Dialogue tracks, and you can see that they're all summed through the Dia ∑ aux track that lives at the end of the mix window, along with summing auxes for all SFX, Music, and Atmosphere tracks. If you are using newer versions of Pro Tools you can right click on the output assignment, and click Show Only Assigments To... This will hide (but still enable) all tracks that aren't a part of the signal chain for that assignment.

This will allow you to see only Dialogue tracks, any Dialogue reverb tracks, and the Dialogue summing aux track. Because I like to keep all my summing auxes at the end of the session, I can have the best of both worlds: I can see how everything is coming together when I scroll to the end of the session, or using this tip I can focus on every aspect of the Dialogue all on the same part of the screen. Of course, this also works in the Edit Window, allowing me to dive deeper into editing whatever I feel is needing some work.

To get back to where you started, just right click on the output assignment again and select Restore Previously Shown Tracks.

Another aspect of this tip is that if you're using aux tracks to sum all of your audio, you can quickly focus on fine-tuning the final pieces at the summing stage while keeping an eye on the final output.

As you can see, I have all my final summing auxes next to my final output aux and my print track. These are at the end of my session, and are tracks 134 through 139. With two clicks I can go from that to seeing only those tracks, which are now tracks 1-5.

Mastering For Fun. Not Profit.

Right off the bat, I should tell you I'm not a mastering engineer. I know too much about the 'black art' of mastering to know that I have no place doing it. That said, in my mind the line between mixing and mastering is much more vague than ever before. I consider myself a mixing engineer, but I will craft my mixes with mastering in mind, and will try to coax things to a place where a mastering engineer won't have to do too much to fix my mixes. It's already competitive enough in this field, and I need to be able to make my clients feel like they're getting everything they pay for. Sadly, the pay usually stops at the mixing process, and I find myself doing quasi-mastering for clients, since a lot of them don't understand that mastering should be an additional step. C'est la mixing vie...

I recently tried my hand at doing some 'serious' mastering, in competition with a friend of mine. We both used the same 2-track mix, which neither of us mixed but were close to the project. We gave ourselves a couple hours, so I didn't get a chance to do all the requisite listening tests in various environments (listening through an open door in another room being a particularly revealing test). I figured I had the opportunity to try some new techniques that I haven't really used in a mastering sense. Here's a look at what I did:

First, a bit about the session itself. I had two tracks of the original mix, using one as a reference of where I started off. I also imported some other reference tracks to see how far I might have to go. There are three ways in which the audio flowed: the original audio track, which then had three tracks of parallel processing being sent to from sends, and which all flowed into another final aux track where more processing was applied.

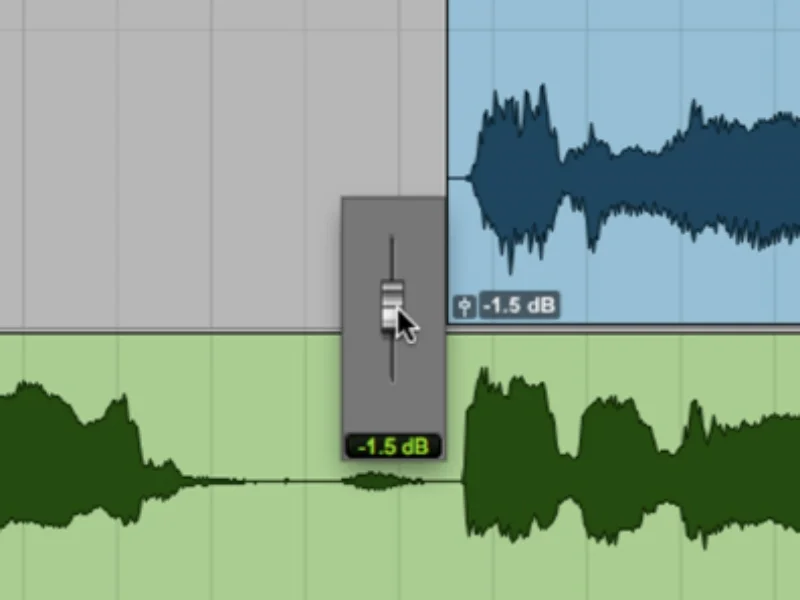

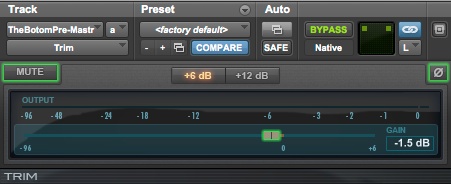

I added a little Avid Trim plugin because I wanted to be able to have some control over how hard I was hitting the first plugin in the chain, the Slate Digital VCC, and I pulled the original mix back -1.5db, just because I felt I was starting off a bit too hot.

I then added the Slate Digital VCC, which I set to an API setting and increased the drive a little bit, just to add some harmonics and saturation. The API setting helps to tighten things up in the lower mids, but still adds plenty of harmonics, so it's not as clean as the SSL setting on the same VCC plugin. I originally set it to a Neve setting but found it too unruly and hairy in the lower mids, and I knew that this track needed those areas tightened up.

Next I added some very specific cuts using the brilliant Plugin Alliance bx_hybrid mastering eq. This eq has a great feature in which selecting any frequency knob shifts that band into a very tight Q boost and you only hear what lies inside that very narrow boost. It's great for finding problem areas and really zeroing in on them. I found a boom at 70Hz, again at 372Hz, and found some nasty sibilance/cymbal zing at 10KHz. At this stage of processing, I find that cutting out bad frequencies is much better than boosting good frequencies, as now things sounded more evened out, using the more transparent technique of cutting with EQ rather than boosting.

Another nice aspect of the bx_hybrid plugin is that there is a very transparent stereo widening control, and I used it to add some width. This added more spread to the stereo field, but it also helped by making some more room up the middle by clearing some things further out towards the side. There was also a very deep 18db/octave lo-cut at 26Hz, just taking out any subsonic rumble that could be eating into my headroom. While we may not be able to hear it, that doesn't mean it's not there. Since this song had some quite aggressive synth bass parts, along with some deep kick samples, and since they were in stereo I used the Mono-Maker feature to make anything below 60Hz mono, and this seemed to do a little to help stabilize the real low end. That's a little technique I lifted from the days of transferring songs to vinyl, since having irregularities in very low frequencies could make the needle jump out of the groove.

So far I haven't done anything dramatic at all, merely adding some harmonics and tightening up the sound. It was only at this point I felt I could do some additive EQ. I turned to a very simple yet great sounding EQ, the Maag Audio EQ4.

I assume this is a vaguely Neve based plugin, but what matters is how it sounds, and this guy sounds great for what it can do. I added 1dB of 40Hz, took out 1dB of 2.5KHz, and added 5dB of 40KHz. Yup, 40KHz. Don't ask me why, nor how, but it can really add a great professional sounding sheen to things. It's called the Air Band for a reason.

The only other things I added on the original track was the Massey L2007 Limiter, not doing anything other than making sure I wasn't clipping before my next gain stage. I think I had the output set to -.1dB, and I honestly don't think it was doing anything, but it was more of an insurance policy. Last in line was the Brainworx bx_meter, showing me the levels of processing I was adding, and I kept it onscreen the whole time. I could have set the meter to show me many different kinds of metering, including the range of Katz K-Meters, but I kept it to dBVU since I was only concerned with the final output.

At this point I thought I'd do some experimenting. I had read about mixing engineer Michael Brauer's method of using many compressors in parallel, and sending different stems and instruments through them before finally summing them at the output stage. You can find more than that basic explanation here.

I ended setting up three aux tracks, each with different compressors designed to work on different aspects of the mix. First up was my go-to compressor, the FET Compressor from Softube. Obviously it's an 1176 clone, but there are some added controls that make it so versatile.

It's set up aggressively, with a fast attack and fast release, which on this plugin is very fast. Unlike most plugins that have a sidechain input (but not the original 1176 hardware unit) this one has a built-in high and low cut that only affects how this compressor reacts. Using a lot of cutting, I got the FET Compressor to really grab onto the midrange of the song, and really start pushing it into an in-your-face sound. Because it's on its own aux track, I slowly pushed the fader up until I started hearing it. The final fader setting was somewhere around -25dB, so it's only a very small part of the overall sound, but very effective in making the heart of the song sound more exciting.

I wanted to make the drums and transients pop a little more, so I turned to a great drum compressor, the Sonnox Inflator. I pushed up the Effect fader and especially the Curve fader, which makes things a bit brighter and 'pokier'. Again, since this was in parallel I only added enough to gain a punchier drum sound, and I think the aux track ended up somewhere around -20dB.

For my next trick, I felt that I was losing some of the immediacy of the female vocal track, so I looked for some way to bring that back, but EQ would also accentuate the snare and guitars. I tend not to use multi-band compressors a lot, but I knew there was an extreme preset on Waves' C4 Multi-Band Compressor that could work.

The original track and the three parallel tracks all summed to another aux track, on which I added some more processing. First up was the Slate Digital VCC Buss plugin, again set to an API setting, with the Drive pulled back just a little.

Next was another instance of the bx_meter mastering EQ, doing some more small cuts. You're probably thinking this is too many plugins, but I feel that it's the opposite of death by a thousand cuts, rather, since I'm only asking each plugin to do a little bit of work, no one plugin is doing any heavy lifting and it all adds flavor and spice and everything nice.

It's pretty extreme compression in the high end, but by adding just a little bit in parallel I found it acted like an Aural Exciter, just putting back some energy into making the vocals pop out with some more diction and immediacy. The parallel aux fader ended up around -30dB, so a little bit of a lot ended up sounding good.

Another non-invasive low-cut at 24Hz, just making sure the subsonic range stayed clean, then a 1.2dB cut at 75Hz, and some more cutting at 210Hz and again at 4.9KHz, taking out some edginess I was hearing. I felt I could add a little bit more width, so I added it at this stage.

Now for my final bus compressor, which in actuality is three different compressors, mangled together into the beast known as the Slate Digital VBC. I rearranged the order in which I hit the compressors, having it hit the FG-Red compressor first, just to tickle the transients and add some energy. A 2:1 ratio and medium attack time meant it wasn't too aggressive. I also set a pretty high high pass filter so that it wasn't triggered by the massive kick sound I already had going.

Moving on, I had the signal hit the FG-Grey compressor, which is a clone of the classic SSL Bus Compressor. Here's where I added some aggressiveness, with a 4:1 ratio and fast release. No high pass filter meant that I was getting some pumping from the kick drum, which is what I wanted. I liked the sound, but ended up backing off on the Mix control, to add more of the original signal back in.

The final stage of the compressor was Slate's version of the ultra-rare Fairchild 670 compressor. I usually look to a Fairchild to smooth things out and add heft and warmth, but I decided to try a different route. This plugin can do Mid/Side compression, where I could address things in the mono field separately from the stereo field. I wanted to make sure that the vocals, bass, kick and snare stood out, and since these were all mono sources panned up the middle I added some compression, maybe 2-3dB at the loudest parts of the song, with only a dB or two of make-up gain. All this did was make those mono elements pop with a little more excitement, while the stereo field of guitars, cymbals, keyboards and synths kept their same dynamics. The Side compression wasn't doing anything, since I only wanted to effect the Mid signal.

At this point I was very very close to being happy with the final mastering job I'd done, but I wanted to add one more flavor over the entire mix, and that was the Slate Digital VTM. I backed off the Input so it wasn't being hit too hard, but with normal bias, at 30ips and a 2" 16 track machine, I found it softened the high end just a little, added a little bass saturation, and just gave it a little more energy overall.

My final plugins were another Massey L2007, not doing anything other than making sure no quick transients clipped the final output. Another bx_meter was kept onscreen to see how the different gain stages were interacting, and that's it. Lots of plugins, I know, but I think the end result was pretty tame considering how many plugins I ended up using. Since they weren't doing much, they all just added layers of flavor and energy.

Here is the full un-mastered song, as mixed by Ryan and Shawn.

Here's the full song after the mastering job I quickly did. It sounds very different than the un-mastered version, but if you've been playing the audio files that accompany each processing stage I think you'll see that I'm not asking any particular plugin to do too much, and I think that that philosophy gives pretty decent results.

Again, I want to stress that I am not a mastering engineer, and that this was done in a couple hours on a dare from a friend, so I used some techniques that are a bit strange, just because I wanted to see how they would work. Thanks for reading this very long article.

Using Shared Reference Images Between Aperture and Capture One Pro

I've been using Aperture as my primary Digital Asset Manager for many years now, but I've recently started to branch out into using Capture One Pro for a lot of my RAW image conversions. Aperture's strengths are in areas like deep asset management/metadata, overall depth of adjustments, and the way its various GUI's are easily pulled up and sent away with the press of one button. Where I find Aperture to be lacking is in a couple of "finishing" steps, like output sharpening and exporting multiple sizes/resolutions simultaneously. This just happens to be some of the big strengths of Capture One. Here's how I've reconfigured my entire library to easily take advantage of using two different RAW convertors.

My work computer is a Mac Pro, connected to a RAID 5 SAN, with a 4 drive RAID 0 internally set up for maximum speed. All my different bits of work reside on the internal RAID 0, which is regularly backed up to the RAID 5 SAN. Originally, when I was just using Aperture for my DAM (digital asset management) I was importing all my photos as managed files, meaning that Aperture created one large library that contained everything, my RAW photos, JPEG previews, metadata, adjustments etc... This is a great no-hassle way of doing things, and is how I operated for years. The problem with starting to use Capture One is that I wanted to be able to share all my original RAW files with both applications. This is where using Referenced Images comes into play.

Referenced Images refers to (no pun intended) setting up your own system of DAM and telling your software to 'refer' to those files instead of importing them directly. Things can get a little tricky, and due diligence is required to make sure nothing gets out of place or not backed up properly, but for what I'm trying to achieve, it's the only way to be.

As you can see, this is a birds-eye view of my folder setup for all my photography. The most important thing is my RAW Archive. In here, I've arranged all my RAW photos by either project or year. Every client gets their own folder under "Client', and all my general shooting gets placed by year, month, and day. From this RAW archive, I can point both Aperture and Capture One to refer to the same photographs, therefore the only thing inside the Aperture folder is my Aperture library holding all the adjustments, previews and metadata. Inside the Capture One folder is my C1 libraries with all the adjustments I make living inside those C1 libraries.

Once I finish editing all my choice photographs, whether that be through Aperture or Capture One, I export the finished products to the Output folder, with sub-folders for large format printing, web uploading, etc...

This is a pretty involved workflow, but once it's put in place, I find that the benefits are easy to reap, and it is a very solid system of managing all my photographic assets. Nerdy, I know, but a lot of photographers who don't have a system in place have trouble finding things and it becomes very easy to lose stuff amidst the thousands of photographs we might take in a year, or sometimes even in a month.

Favorite Compressors Part 1

I thought I would take a second and share some of my favorite bits and bobbles of plugin gear, starting off with some of my favorite compressors. I find that compressors can be some of the most misunderstood and misused pieces of audio gear out there, but they're really important and I couldn't do a mix without them. Well, I could, but I really wouldn't want to.

Up first is a compressor that I probably use more than any other on a given mix: the FET Compressor by Softube.

As you can see, it's an 1176 style compressor, with a bunch of added modifications. As with most 1176 style compressors, this one moves fast and is quite grabby, like a Black Friday event at Walmart, but much better and with less greed. It's speed and overall aesthetic makes it great for drums, which is something I always try putting it on, almost as de rigueur. It works much more often than it doesn't, which may sound like a backhanded compliment, but that's the best sign of a great piece of gear in my opinion. It's a staple on snare drums, and the built-in parallel feature means that it's great for drum bussing as well. Combining the "All Buttons In" with the low cut set pretty high makes for a stupid sound (but in the best possible way), and turning the parallel knob all the way up, then backing it off until it feels just right is a great way to retain clarity with added mayhem.

Another common use I've found for the FET Compressor is on vocals, especially female rock vocals. It can give you a really great modern vocal sound, punchy and in your face, and bring out all the little details in a voice. Again, having the low and high cut in the detector signal really makes it powerful, so instead of using the low cut to stop a kick drum from triggering the compressor, I sometimes use the high cut to help stop the sibilance from a vocalist splattering all over the compressor. I also tend to dial in a very fast attack and release for rock vocalists, and turn up the parallel knob to bring back some of the original flavor. A lot of times I'll end up using this compressor on a vocal to bring up the details and make it punchy, then add a slower compressor afterwards to smooth things out.

Fire and Ice

The other weekend Chicago witnessed a very bizarre occurrence. A warehouse, located in the Bridgeport area, caught fire and it quickly spread throughout the facility. Firefighters did what they could to battle the blaze, but freezing temperatures meant that their efforts to douse the flames in water led to huge sheets of ice encapsulating the entire building. You can read more about it here.